Rather than ordering or stockholding replacement parts, some pilot schemes in the bus and coach industry are making one-off spare parts using a plastic or metal 3D printer. In a feature article on the subject for Transport Engineer magazine, John Dwight, Sales Director, Imperial Engineering, gives his views on where this technology might be most useful, its future potential as well as limitations.

“The automotive industry has been at the forefront of 3D printing and technology in general, for many years experimenting with various applications for product development, as well as efficiencies to the supply chain.

As one might expect, Formula One race teams were an earlier adopter of 3D printing, driven by the need to produce F1 car parts quickly and economically, whilst reducing weight but without compromising strength or integrity. This has since become more mainstream within the wider automotive community, in the pursuit of lighter, cheaper parts.

On the face of it, the concept of additive manufacturing, whereby components are created layer by layer rather than subtractive manufacturing, where material is extracted from a block, is highly attractive to the bus and coach sector for a number of reasons.

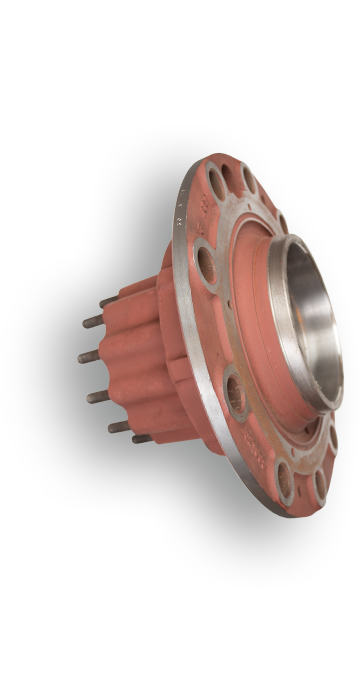

Cost-effective prototyping for one. The flexible nature of the technology and extensive design freedom enables new innovations and enhancements to existing parts to be produced quickly and more sustainably, as the process significantly reduces material wastage. Equally, it would be particularly useful for producing bus parts that are now obsolete or no longer manufactured, applicable for historic vehicles, for example. There continues to be demand for these parts but stock is often hard to source and very expensive.

Secondly, light-weighting of parts has huge benefits to both environmental performance and operational costs. 3D printing certainly presents a compelling opportunity for bus and coach manufacturers to reduce vehicle weight and deliver better fuel efficiency without compromising on power and reliability.

As well as making parts lighter, there’s also an opportunity for components to be consolidated into single assembly units, which again has positive cost implications from both a manufacturing and operational perspective.

At the moment, however, 3D printing does have its limitations in a PSV context. Scalability is certainly one issue, as historically this technology has been aimed at low volume or single batch production, which is why it’s attractive to sports car manufacturers and F1 teams.

There’s also the issue of strength and durability of parts produced by additive manufacturing, in respect of the integrity of layering material. Buses and coaches are high-mileage, all weather vehicles, so given the regulatory demands on the industry in terms of safety, there would need to be an extensive testing period for 3D printed parts and strict quality controls put in place, before there’s a move away from traditional OE manufacturing. This would also most certainly require certification of 3D printed parts and approval of the companies supplying them.”